The FuelEU Maritime initiative is a key part of the European Green Deal and the Fit for 55 packages, aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting sustainable practices in the maritime sector. The initiative seeks to reduce the carbon intensity of maritime fuels and increase the use of renewable and low-carbon fuels.

1. Legislative Background

Key Provisions: The FuelEU Maritime Regulation (EU 2023/1805) is an EU law adopted under the “Fit for 55” package, aimed at decarbonizing maritime transport. It establishes limits on the greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity of energy used by ships during voyages involving EU ports. The GHG intensity is measured on a well-to-wake basis (accounting for emissions from fuel production to combustion) and is expressed in grams CO₂ equivalent per megajoule (gCO₂e/MJ). The baseline is the average fleet intensity in 2020 (91.16 gCO₂e/MJ), and ships must progressively reduce their GHG intensity relative to this baseline by set targets: 2% by 2025, 6% by 2030, 14.5% by 2035, 31% by 2040, 62% by 2045, and 80% by 2050. These targets mandate increased use of renewable and low-carbon fuels (like advanced biofuels, e-methanol, e-ammonia, hydrogen, etc.) or other emission-reduction measures over time.

Scope: FuelEU Maritime applies to all ships above 5,000 gross tonnage (GT) carrying passengers or cargo for commercial purposes, regardless of flag, when they use EU ports. Specifically, it covers:

- 100% of energy used when at berth in an EU port;

- 100% of energy used on voyages between EU ports;

- 50% of energy used on voyages where either origin or destination (or one leg of the journey) is an EU port, and the other is a non-EU port;

- 50% of energy used on voyages to/from certain outermost EU regions (e.g., Canary Islands, French overseas territories).

Exemptions: Warships, naval auxiliaries, fishing vessels, non-mechanically propelled vessels, and government ships (non-commercial) are exempt. EU Member States may also exempt certain small island, or outermost region voyages until the end of 2029 under strict conditions.

On-Shore Power and Zero-Emission Tech: From 1 January 2030, ships at berth in major EU ports must use onshore power supply (OPS) or zero-emission technologies for their electricity needs. This applies to ports covered by the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR) Article 9 (typically core TEN-T ports for passenger and container ships). OPS exemptions exist for stays under 2 hours, emergencies, or if OPS is unavailable. If a ship uses a certified zero-emission technology (like battery, fuel cell, or wind power that emits no GHGs or air pollutants), it can be exempted from connecting to OPS. This requirement pushes investment in port electrification and ship-side equipment by the end of the decade.

Enforcement Mechanisms: FuelEU Maritime enforcement relies on a monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) system aligned with the existing EU shipping MRV (Regulation 2015/757). From 1 January 2025, ships must continuously monitor and record fuel/energy usage and other voyage data. After each calendar year (reporting period), an emissions report must be submitted to an accredited verifier by 31 January, and the verified FuelEU report and calculated GHG intensity are recorded in an EU database by 31 March. By 30 June following the reporting year, if the ship meets requirements, the verifier issues a FuelEU Document of Compliance, which the ship must carry from that date onwards when visiting EU ports.

Compliance and Penalties: If a ship exceeds the allowed GHG intensity (i.e., has a “compliance deficit”) or fails to use OPS when required, the company will incur a FuelEU penalty. The penalty is designed to be dissuasive and remove any economic advantage from non-compliance. Annex IV of the regulation provides formulas for calculating penalties. In simple terms, for GHG intensity non-compliance, the fine is proportional to the difference (in MJ of fuel or CO₂eq) between the ship’s performance and the target, multiplied by a fixed factor meant to approximate the cost of cleaner fuels. Industry estimates indicate this equates to roughly €2,400 per ton of fossil fuel over the limit in 2025. The exact rate can be adjusted over time to reflect energy prices. Penalties increase for consecutive non-compliance periods: if a ship fails to meet targets multiple years in a row, the fine for the later years is multiplied by an escalating factor.

There is also a separate penalty formula if a dedicated sub-target for Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin (RFNBO) is triggered after 2034 (a 2% RFNBO usage mandate, if market conditions warrant). Additionally, each non-compliant port call (i.e., not using OPS when required) carries a fixed penalty per port call, roughly calibrated to the cost of shore power (the regulation mentions a fixed amount in EUR per kWh of shore power not used). Penalty revenues will be used to support maritime decarbonization (reinvested in promoting renewable fuels and helping the sector meet climate goals).

Enforcement authorities: EU Port State Control will check for compliance documents as part of inspections (the FuelEU compliance document is added to the list of certificates in Directive 2009/16/EC on port state control). If a ship persistently does not comply (e.g., fails to rectify deficits or pay penalties), authorities can ultimately issue an expulsion order. Member States may refuse entry to ships that are under an expulsion order due to repeated non-compliance, effectively barring them from EU ports until they fulfil their obligations. This creates a strong legal incentive to comply, on top of financial penalties.

Timeline Summary: The regulation enters into force on 1 January 2025. The first monitoring period begins in 2025, with initial reports due in early 2026 and the first compliance documents required by mid-2026. OPS usage becomes mandatory in 2030 for applicable ports. The GHG intensity targets tighten at 5-year intervals through 2050. There are also interim reviews: by the end of 2025, the Commission will list certain non-EU transshipment ports (to prevent evasion via nearby hubs), and by 2027-2028 there will be an assessment of the rule’s effectiveness, possibly adjusting the RFNBO sub-target or other aspects.

FuelEU Maritime works in conjunction with the EU Emissions Trading System (which began covering maritime emissions in 2024) as a complementary measure – ETS puts a price on CO₂, while FuelEU directly forces the use of cleaner fuels through intensity limits.

2. Impact Analysis

On Shipowners: Shipowners will face significant financial and operational impacts. They must invest in cleaner technologies and fuels to meet the GHG intensity limits, or else pay penalties. This means evaluating options like installing alternative fuel capability (e.g. LNG, methanol, ammonia-ready engines), energy efficiency upgrades (wind-assisted propulsion, air lubrication, etc.), or purchasing biofuels and e-fuels for compliance. Existing ships may require retrofits or may become less competitive if they cannot economically meet the targets. Owners will also need to update contracts to allocate responsibilities and costs of compliance. Notably, FuelEU designates the “company” (usually the ISM Document of Compliance holder) as the responsible entity – often this is the technical manager or operator, not necessarily the registered owner. However, the ultimate costs will likely be borne by whoever pays for fuel and voyage decisions. Owners under time charter may seek contract clauses ensuring charterers use compliant fuels or compensate for penalties. If an owner operates the ship (in voyage charter or liner trades), they will directly face fuel procurement decisions: burn cheaper fossil fuel and pay penalties (and potentially face EU ETS costs) or invest in cleaner fuels/tech now.

Financially, operating costs are expected to rise. Low-carbon fuels today are significantly more expensive than traditional heavy fuel oil (HFO). For example, e-methanol or bio-methanol can cost several times more per ton than HFO. The regulation’s design tries to eliminate any savings from non-compliance by setting penalties roughly equal to the cost difference. For instance, a legal commentary indicates a penalty around €2,400 per ton of non-compliant fuel in 2025, which is on the order of the price premium for some biofuels. This means if fossil HFO is €600/ton and a biofuel alternative is €1,200/ton, the penalty (~€2,400/ton for excess emissions) would outweigh the cost of using the cleaner fuel – nudging owners to choose the cleaner option. Over time, as targets tighten (e.g. 6% in 2030, 14.5% in 2035), the required fraction of alternative fuel or efficiency gains grows, raising both compliance costs and the stakes of non-compliance. Owners also must consider capital expenditures: newbuild ships with dual-fuel or zero-carbon capability are more expensive. Studies show a dual-fuel vessel might incur 3–6% higher total cost of ownership if initially run mostly on fossil fuel due to higher capex, but it provides flexibility to switch to cheaper alternative fuel in the future, potentially yielding net savings over the vessel’s life once e-fuels become cost-competitive. Owners who invest early in “future-proof” ships could gain a first-mover advantage by avoiding retrofitting costs later and commanding premium charters from eco-conscious customers. Indeed, more than half of newbuild orders in early 2024 were already for methanol-capable ships, indicating owners are anticipating FuelEU and similar rules.

Operationally, shipowners will need to adjust voyage planning and operations. They might implement slower steaming to reduce fuel burn (hence emissions), optimize routes to minimize time in EU waters on fossil fuel, schedule more frequent maintenance (e.g. hull cleaning to reduce drag), and ensure onshore power compatibility to avoid port call penalties after 2030. There could also be a fleet deployment impact: ships that cannot easily comply may avoid EU trades or be concentrated on non-EU routes, while the newest, cleanest ships serve EU ports to meet the regulation. In the long run, the regulation will likely accelerate fleet renewal – older, less efficient tonnage could be phased out earlier than otherwise because the cost to upgrade or the penalties make them uneconomical. This might reshape asset values: fuel-efficient or alternative-fuel ships may appreciate relative to conventional ships as 2025 and 2030 deadlines approach, influencing second-hand prices and charter rates.

On Charterers: Charterers (especially time charterers who hire ships and provide fuel) will be heavily impacted in terms of fuel procurement and voyage instructions. Under the “polluter pays” principle, the entity deciding on fuel purchase and vessel operation is intended to bear the cost. Often that is the time charterer (they buy the fuel and direct the ship’s speed, route, etc.). Contracts are already being updated (e.g. the new BIMCO FuelEU Charter Clause) to clarify how compliance costs and liabilities are split between owner and charterer. We can expect clauses that require charterers to use fuels that enable the ship to meet the GHG intensity limit or else indemnify owners for penalties. For charterers, this means higher voyage costs when using EU ports: they may need to bunker more expensive low-carbon fuels or blends for the European leg of voyages. They will likely integrate FuelEU considerations into their voyage planning – for example, a charterer might decide to refuel with a biofuel blend before entering EU waters to ensure compliance, or adjust a ship’s itinerary to include a non-EU transshipment (though the regulation tries to negate this advantage by counting 50% of energy to/from nearby non-EU hubs).

Financially, charterers will evaluate the cost-benefit of cleaner fuel vs penalties. If the market price of compliant fuels (considering energy content and GHG factors) is lower than the effective penalty per ton of fuel, the rational choice is to use the compliant fuel. Initially, some charterers might opt to pay penalties if alternative fuels are scarce or extremely costly. However, the escalating nature of penalties and addition of EU ETS costs on CO₂ (around €90/ton CO₂ in 2024, phased in for shipping) means running purely on fossil fuel will become increasingly expensive. Charterers that proactively secure supplies of biofuels or e-fuels via contracts (offtake agreements with fuel providers) could gain a cost advantage. They may also favour ships with dual-fuel capability – for instance, a charterer might choose a vessel that can burn methanol or LNG, giving flexibility to meet FuelEU targets by switching fuels as needed.

Legally, charterers must be mindful that non-compliance can disrupt operations. A ship without a valid FuelEU compliance document by mid-2026 could be detained or denied entry in EU ports. If a charterer’s actions (e.g., fueling with only heavy oil) caused the ship to fall out of compliance, they could be liable for breach of charter. Therefore, charterers are incentivized to collaborate with owners and technical managers on compliance strategies. In practice, we may see voyage charter rates start to factor in FuelEU compliance – e.g., a freight contract to/from the EU might include surcharges for using cleaner fuel (like how ECA sulphur regulations led to bunker adjustment factors).

On Ship Technical Managers (ISM managers): Technical managers often hold the International Safety Management (ISM) Document of Compliance for the ship and thus are the “company” responsible to authorities under FuelEU. This puts legal compliance responsibility on them, even if they don’t pay for fuel. They must ensure monitoring plans are in place, data is collected and reported accurately, and the ship meets the requirements (or timely reports any non-compliance). This significantly increases the administrative burden on managers: they will gather fuel consumption data, likely using automated systems and reporting software (integrating with EU databases). They will liaise with verifiers to get annual reports audited and compliance documents issued. Technical managers also may need to advise owners on technical measures to improve GHG performance (since they handle day-to-day ship operations and maintenance).

Operationally, technical managers will implement Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plans (SEEMP) that incorporate FuelEU targets. They might deploy data analytics to monitor the ship’s carbon intensity in real time and adjust operations (speed, engine settings) to stay within limits. Crew training is another implication – crews need to understand fuel switching procedures, energy-saving practices, and the importance of accurate record-keeping for FuelEU. The managers will coordinate any equipment upgrades (e.g., installing shore power connections, energy-saving devices, or trailing new fuels) to ensure compliance.

Financially, many technical managers operate under fixed fees per day from owners. With FuelEU, they may charge additional fees for compliance services, as suggested in industry guidance. They also face liability exposure: if a manager fails to properly monitor or report, leading to penalties or ship detentions, they could be held accountable by the owner. Therefore, managers will likely insist on strong indemnity clauses and perhaps performance bonuses for compliance. Some managers might seek insurance or guarantees to cover potential penalties (especially since they might have to pay first then reclaim from charterers/owners). For example, a manager might require an owner to provide funds or security to cover a compliance deficit of the ship, given the fines can accumulate if a vessel is far over the limit.

Compliance Constraints: The industry faces several constraints and challenges in complying with FuelEU Maritime:

- Technical Constraints: Not all low-carbon fuels or technologies are mature. For instance, ammonia-fueled ships are still in development and expected around 2027. Battery or hydrogen fuel cells are only feasible for smaller ships or short voyages currently. This limits immediate options largely to biofuels, LNG (which still has some GHG benefit but mainly methane slips concerns), or methanol. Retrofitting existing ships for new fuels (like converting a diesel engine to methanol) can be expensive and time-consuming. Additionally, fuel availability is a constraint: the supply of sustainable biofuels and e-fuels is projected to fall short of demand for 2030 targets, meaning ship operators might struggle to purchase the needed volumes of clean fuel in the early years. There’s a “chicken-and-egg” dilemma where fuel producers wait for demand and shipowners wait for supply. FuelEU attempts to break this by guaranteeing demand via regulation, but ramping up production takes time.

- Operational Constraints: Bunkering infrastructure for new fuels is limited. Not all ports can supply methanol or biodiesel, let alone hydrogen or ammonia. Ships trading globally can’t rely solely on EU ports for fuel, so if they install, say, a methanol engine, they must plan carefully where to bunker. Using OPS in port requires compatible equipment on the ship and available power on the pier – ports are racing to install OPS for 2030, but until then, not every required port has it ready. There’s also a voyage planning aspect: half of energy on voyages into/out of the EU is counted, meaning even non-EU legs matter. Companies might consider slightly slower speeds to reduce fuel use (hence emissions) within the portion counted by FuelEU, though this must be balanced against commercial pressures. Weather and delays can affect fuel consumption; a harsher voyage could raise GHG intensity unexpectedly, so there’s inherent variability to manage.

- Financial Constraints: The cost of compliance can be heavy, especially for smaller shipowners or those with older fleets. Alternative fuels can be 2-5 times more expensive than HFO per energy unit in current markets. Upgrading ships (or ordering new ones) requires capital and confidence in future regulations. Some owners may face financing challenges to fund green retrofits or newbuilds. While FuelEU penalties create a downside, there is still uncertainty on future fuel prices and technology, making it a financial risk to invest early. However, there are also opportunities to tap into EU or national funding: for example, the EU’s Innovation Fund, Connecting Europe Facility (CEF), or national green shipping programs might subsidize alternative fuel projects or OPS installations. Moreover, since penalty revenues are earmarked for the sector’s decarbonization, shipowners could indirectly benefit from grants or incentives funded by those who paid fines (a sort of recycling of funds).

- Legal and Contractual Constraints: The multi-stakeholder nature of shipping (owner, technical manager, time charterer, voyage charterer, fuel supplier) means legal ambiguity if not clarified. The BIMCO FuelEU clause and other contractual templates need to be adopted swiftly to assign responsibilities for providing compliant fuel, preparing monitoring plans, and paying for penalties or rewards. There may be disputes initially as to what constitutes compliance – e.g., if a time charterer fails to meet the required fuel mix, does the owner have the right to refuse orders? The regulation also allows the responsible party to be different by contract (e.g., an owner could contractually pass on penalties to a charterer or even a fuel supplier if fuel quality was not as promised). But these require careful drafting and negotiation, which is a constraint given the short time before enforcement. For technical managers, new clauses in management agreements are needed to cover their role and compensation.

Opportunities for First Movers: Despite challenges, FuelEU Maritime creates opportunities for proactive industry players:

- Competitive Advantage: Shipowners who act early to comply can market their services as “green shipping,” potentially attracting customers (charterers or cargo owners) with sustainability goals. They also avoid penalties, which could become a significant expense for laggards. For example, a container line that switches a portion of its fleet to bio-methanol might win long-term shipping contracts from big retailers aiming to decarbonize their supply chain.

- Pooling and Credits: The regulation uniquely allows compliance pooling across ships. A “first mover” ship that is well below the GHG intensity limit (e.g., a ship running on 100% e-methanol) generates a compliance surplus. This surplus can be transferred or sold to other ships (even from different companies) that have a deficit. This mechanism is akin to credit trading and rewards over-compliance. A company with multiple ships can pool internally (balancing out greener and less-green ships), or a green ship owner could sell credits to others, creating a new revenue stream to help offset the cost of the clean fuel.

- Technological Leadership: First movers that invest in new technologies (like dual-fuel engines, wind-assist, advanced energy management) gain valuable operational experience. As the whole industry eventually needs to adopt these by 2030s, those early adopters could become leaders, setting standards and possibly influencing regulation. They might also secure favourable terms with equipment manufacturers or fuel suppliers by being launch customers. For instance, ordering dual-fuel ships now secures earlier delivery slots and avoids anticipated shipyard capacity constraints in the late 2020s when many will rush to retrofit or build new.

- Access to Finance and Funding: Banks and financiers are increasingly concerned about “stranded assets” in shipping. Companies with clear decarbonization strategies (aligned with regulations like FuelEU) may find it easier to obtain financing or at better rates (as seen with sustainability-linked loans or Poseidon Principles signatory banks). Additionally, first movers could qualify for demonstration project grants or R&D partnerships (e.g., the EU might sponsor pilots for new fuel usage on commercial routes).

In summary, while FuelEU Maritime imposes costs and challenges, it also incentivizes innovation and early action. Shipowners, charterers, and managers that adapt quickly can turn compliance into a competitive edge, whereas those who delay may incur higher costs or operational restrictions in the future.

3. Compliance Strategies

Achieving compliance with FuelEU Maritime will require a combination of technical, operational, and managerial strategies. Below are best practices and strategies stakeholders can adopt:

Data Collection & Analytics: Accurate data is the foundation of compliance. Companies should implement robust fuel consumption monitoring systems (flow meters, fuel tank gauges, emissions sensors) and integrate them with electronic logbooks and reporting software. Many are enhancing their MRV (monitoring, reporting, verification) processes from the EU MRV and IMO DCS schemes to also calculate FuelEU-specific metrics. Best practice is to use real-time data analytics: for example, a dashboard that tracks a ship’s current GHG intensity (gCO₂e/MJ) against the required target, updating as fuel is consumed. This allows crews and managers to take corrective action during operations rather than discovering non-compliance at year-end. Big data analysis can also help identify inefficiencies – analyzing voyage data to find where fuel consumption was higher than expected (e.g., due to weather or suboptimal routing) and then mitigating those factors on future voyages. Early adoption of software tools (some classification societies and tech firms are offering FuelEU Maritime calculators and compliance trackers will ease the reporting burden and reduce errors. Shipowners should ensure that monitoring plans are in place and approved by verifiers (such as classification societies or independent MRV verifiers). Regular audits and drills (simulated calculations before official submission) help validate the data collection process, ensuring smooth compliance with regulatory requirements.

Technical Measures & Pre-Planning: It is crucial to plan vessel upgrades and operational changes in advance. In the short term, simple measures can yield the 2% improvement needed by 2025: for instance, using a B5 or B10 biodiesel blend (5–10% biofuel mixed with fossil fuel) could achieve a couple percent reduction in GHG intensity due to biofuels’ lower net carbon footprint. Ensuring ships are well-maintained (clean hull and propeller, tuned engine) improves fuel efficiency and lowers GHG per mile. Many companies are instituting speed optimization policies – known as slow steaming – to reduce fuel burn, especially on intra-EU routes where 100% of emissions count. Before entering an EU emission-regulated voyage, a ship could slow down if schedule allows, thereby cutting fuel use and meeting intensity targets without fuel switching.

Another strategy is fuel switching carrying multiple fuel types and switching to a cleaner fuel for the portions of the voyage that count under FuelEU. For example, a ship could burn LNG or a biofuel blend when departing an EU port and then switch to conventional fuel on the high seas (though note, 50% of that voyage’s fuel will still count). Such switching must be carefully planned (training crew on switching procedures, ensuring compatibility and tank segregation). Shore power readiness is a key compliance area for 2030 and beyond: companies should plan retrofits of shoreside electrical connection equipment by identifying which of their vessels call regularly at ports likely to mandate OPS. Upgrading a ship for OPS (installing high-voltage transformers, connectors per IEC/IEEE 80005 standard) requires yard time and investment, so planning in maintenance schedules (perhaps combining with class renewal surveys) is recommended.

Operational Efficiency: Enhanced voyage planning and operational optimization will be central. Weather routing to avoid heavy weather can save fuel. Optimizing arrival times to reduce waiting at anchor (thus avoiding unnecessary fuel use) also helps – if a ship can arrive just-in-time, it can sail slower (burning less fuel and emitting less). Port operations should be optimized: use port equipment or harbour tugs for maneuvers if it saves the ship’s fuel, minimize use of diesel generators by using port power or sharing loads with shore when possible. Trim and cargo planning can reduce resistance; for instance, loading the ship to an optimal trim can lower fuel consumption. Crew awareness and incentives are also effective – some companies implement “virtual reward” schemes where vessels that beat their GHG target get recognition or crew bonuses, fostering a culture of efficiency.

Banking, Borrowing, and Pooling: The regulation allows some flexibility mechanisms that stakeholders can strategically use. If a ship exceeds its target (has a compliance surplus), it can bank that surplus to use next year. If one year falls short, it can borrow from the next year’s target (with a 10% penalty on the amount). Strategically, a company might over-comply in earlier years when it’s easier (e.g. 2025–2026 targets are low) to bank surplus for later tougher years. Pooling compliance among ships (even across companies) is a novel strategy. Industry best practice could involve forming a compliance pool or consortium: multiple shipowners agree to combine their fleets’ results so that as a group they meet the targets even if some individual ships don’t. This requires trust and clear agreements (possibly facilitated by a third-party verifier or exchange platform for compliance credits). Early movers are already exploring this – e.g., large operators with diverse fleets might keep a few green-fueled ships in their roster to balance out others. Charterers and operators can also trade compliance: if an owner knows their ship will be below the limit, they could sell that surplus to a partner’s ship that faces an overage, benefiting both (one gets revenue, the other avoids a larger penalty).

Engagement and Training: Compliance isn’t just technical – it’s also about people. Companies should train shore staff and crew on FuelEU requirements. Workshops and drills on how to fill out FuelEU reports, how to handle verifier checks, and how to respond to port state inspections will build confidence. Sharing best practices within industry groups (like forums under the European Sustainable Shipping Forum, or industry associations) can help stakeholders learn from each other. For example, if one company finds success using a certain biofuel on a route, sharing that info can help others comply and build demand for that fuel.

Collaboration with Charterers/Fuel Suppliers: A practical compliance strategy is to collaborate across the supply chain. Charterers, owners, and fuel providers should communicate early about fuel needs for compliance. If a charterer plans voyages that would push a ship over the GHG limit, they should work with the owner to adjust speed or supply a better fuel. Fuel suppliers can offer turnkey solutions like delivering a specific biofuel blend when a ship refuels at an EU port, along with sustainability certifications needed for the GHG calculations. We see emerging services where fuel suppliers guarantee the GHG performance of their fuel (providing the emission factor data needed for compliance). Some stakeholders might use contractual arrangements (GHG service agreements) where a fuel supplier agrees to bear some liability for penalties if their fuel doesn’t meet the expected spec – effectively guaranteeing the fuel’s performance. While novel, these kinds of agreements can reduce risk for ship operators.

Continuous Improvement Cycle: Lastly, treat compliance as a continuous improvement cycle. Each year’s report from the verifier will show where the ship stands (was there a surplus or deficit, did it meet OPS obligations, etc.). Use that to refine the strategy for next year. Perhaps in 2025 a company learns that one vessel barely missed the target – in 2026 they might allocate a bit more biofuel to that ship or adjust its service speed. By iterating and planning progressively for the stricter targets, stakeholders can avoid nasty surprises. Essentially, don’t wait – act, learn, and adjust each year rather than deferring action until just before 2030 or 2035 deadlines.

In summary, proactive planning and operational excellence are the pillars of FuelEU Maritime compliance. Those who integrate data-driven decision making with smart operational tweaks and stakeholder collaboration will find compliance achievable and even discover efficiencies that offset some costs. It’s about embedding the FuelEU mindset into daily operations – much like safety or pollution prevention is standard practice, carbon intensity management must become a new normal.

4. Roadmap for Compliance

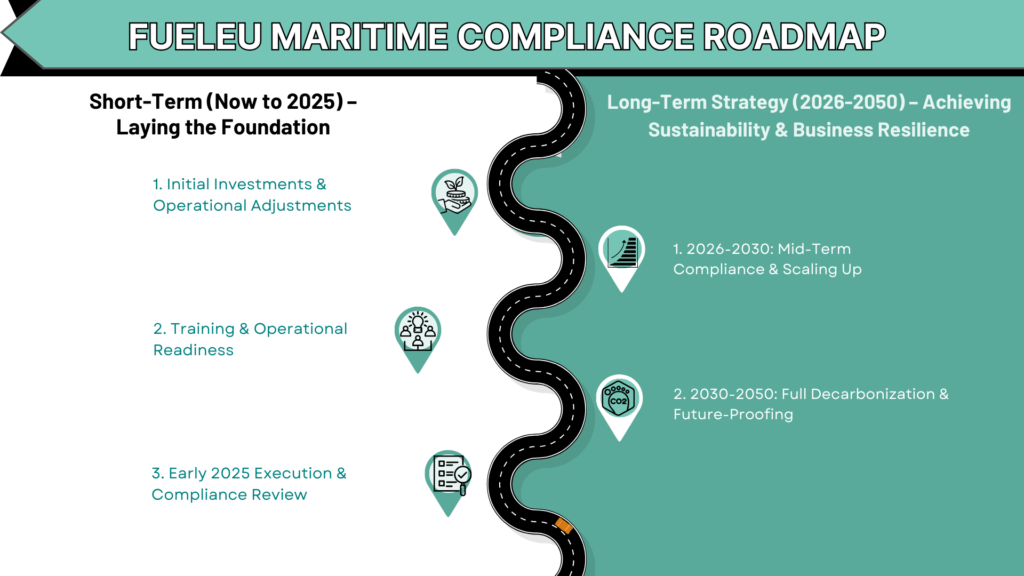

Stakeholders should approach FuelEU Maritime compliance with a phased roadmap, balancing short-term actions for 2025 and long-term strategy up to 2050:

Short-Term (Now to 2025) – Laying the Foundation:

- Initial Investments: Companies have budgeted for and implemented “low-hanging fruit” investments to achieve quick emission reductions by 2025. This included energy-saving measures such as LED lighting, variable speed pumps, and improved hull coatings, along with the initial adoption of alternative fuels. By Q4 2024, many companies ramped up trials of B20 biodiesel or drop-in synthetic fuels, securing sustainable biofuel blends for select voyages to meet the 2% reduction target starting January 1, 2025.

- Early 2025 Execution: From January 1, 2025, companies began monitoring voyages as per the approved plan. Many conducted a dry run of the reporting process in Q1 2025 by generating a dummy FuelEU report to verify data accuracy and address any discrepancies ahead of year-end. By the end of 2025, all necessary data was collected and prepared for submission by the January 31, 2026, deadline.

- 2025 Targets: By end of 2025, companies will work to achieve at least the required 2% GHG intensity reduction through minor fuel and operational adjustments. Meeting or exceeding this target helped prevent compliance deficits in the first year, ensuring regulatory momentum and avoiding the progressive penalty multiplier for repeat shortfalls

- Documentation by 2026: By Q1 2026, work with verifiers to calculate each ship’s compliance balance (difference between required vs actual GHG intensity). Any ship with a deficit should plan how to compensate (e.g., purchase compliance credits from another ship or prepare to pay the FuelEU penalty by June 30, 2026). By 30 June 2026, obtain the FuelEU Document of Compliance for each ship – this document will be needed for port entries and will be checked by authorities.

Mid-Term (2025 to 2030) – Scaling Up and Integrating into Business:

- Increasing Targets: The next milestone is 6% GHG intensity reduction by 2030. Between 2025 and 2030, companies should gradually scale up the share of low-carbon fuel or equivalent efficiency to stay on a trajectory (perhaps 1–2% improvement each year). Do not wait until 2029; it may be prudent to target ~3-4% reduction by 2027, ~5% by 2028, etc., to have a buffer.

- OPS Readiness by 2030: Identify which ships will need to use On-Shore Power from 1 Jan 2030 (likely all frequent callers to TEN-T core ports in the EU). Develop a retrofit program so that by 2028-29, those ships have the necessary onboard equipment. Coordinate with ports on compatibility – some ports might offer incentives or pilot programs earlier. Budget for the costs (OPS retrofits can be several hundred thousand euros per vessel). Also train crew on safe procedures for connecting to shore power.

- Fleet Renewal Strategy: By mid/late-2020s, align newbuild orders or charters with FuelEU goals. For any ship that will operate in the 2030s on EU routes, consider ordering new ships with dual-fuel or zero-emission capability. As of 2024, many new orders were for methanol or LNG dual-fuel ships as a response to these regulations. Plan replacement of older tonnage that would struggle with 2030 targets (for example, an old steam turbine LNG carrier or a 90s-built bulker might be inefficient – decide whether to retrofit or phase out by 2030). Business continuity depends on having a fleet that can legally and profitably trade – so avoid being stuck in 2030 with ships that would constantly incur penalties or be barred from ports.

- Financial Planning: Develop a compliance cost forecast for the next 5-10 years. This should include expected costs of cleaner fuels (net of any EU ETS revenue from free allowances or such, if applicable), the potential penalties if falling short, and capital costs for retrofits. Incorporate the possibility that by 2030, the RFNBO sub-target might kick in, requiring at least 2% of fuel to be RFNBO (green hydrogen-based fuel). RFNBO like e-methanol or e-ammonia could be expensive, so look for funding opportunities: EU programs, green bonds, or partnerships with cargo owners willing to pay a premium for carbon-neutral transport. Also, recall that penalty revenues go into fostering clean fuel use – keep an eye on opportunities to benefit from any subsidy or co-financing schemes that result.

- Stakeholder Engagement: By 2027-2028, engage in policy feedback – the Commission will review the implementation, and industry voices can help shape adjustments (for example, if certain fuels need recognition or if targets seem unattainable, regulators may fine-tune). Also, continuously refine charter party clauses. BIMCO and other bodies will likely update standard clauses as experience grows; adopt those in all new contracts to clearly assign who pays for what (fuel premiums, penalties, rewards).

Long-Term (2030 and beyond) – Sustained Decarbonization & Business Transformation:

- Meeting Steeper Targets: After 2030, the required reductions steepen (e.g., 14.5% by 2035, 31% by 2040, etc.). These levels will likely necessitate significant use of alternative fuels or zero-emission technologies. Long-term strategy should include transitioning to new fuels as they become viable. For instance, plan for some ships to use green ammonia or hydrogen by 2035-2040 for the 31% cut, as drop-in biofuels alone might not suffice at that scale. Fleet renewal cycles (typically 20-25 years for ships) mean that vessels delivered in the 2030s must be essentially zero-carbon by design to hit the 2050 goal of 80% reduction (and beyond, presumably 100% later). So, by mid-2030s, most newbuilds should be running on near-zero carbon fuels. Companies should explore pilot projects in the 2020s so that by the 2030s they have operational familiarity with these fuels.

- Business Continuity and Competitiveness: Embrace that sustainability is core to business. Shipping companies may need to overhaul their business models to remain competitive. This includes potentially offering “green services” at a premium – e.g., a carbon-neutral shipping option where the carrier uses 100% renewable fuel (meeting FuelEU and even exceeding it) for an extra fee. Some cargo owners might pay this, turning compliance into a revenue opportunity. It also means managing the transition risk: as the world (and possibly IMO) moves similarly toward decarbonization, there’s less risk of being uncompetitive by doing the right thing – indeed, not complying would mean being shut out of markets like the EU.

- Penalty Avoidance and Enforcement: In the long term, aim to avoid penalties entirely. Not only are they expensive, but they could also compound: a ship with two consecutive deficits faces higher penalty rates. Moreover, repeat non-compliance could result in expulsion orders, as noted. No company can afford a fleet that is unwelcome in the EU. Therefore, by 2030s, the mindset should shift from “comply to avoid fines” to “comply because that’s how shipping is done.” This likely aligns with global measures – by then, the IMO may have its own GHG intensity requirements and carbon price, which together with FuelEU would drive a universal shift.

- Monitoring Evolution: Continue to adapt compliance management with evolving technology. By 2030s, expect more digitalization and possibly automated verification. The EU may integrate FuelEU reporting with other systems or use satellite data to verify emissions. Companies should stay ahead by adopting advanced MRV tech (some are looking at continuous emissions monitoring sensors on exhausts that feed into cloud databases). These can simplify compliance and provide transparency to customers.

- Alternative Fuels & Efficiency Measures: The roadmap to 2050 clearly hinges on alternative fuels. Methanol, for example, can be a transition fuel (produced from natural gas initially, then moving to bio-methanol, then e-methanol). LNG offers some GHG reduction but likely not enough long-term, though LNG ships could transition to bio-LNG or synthetic methane if methane leakage is solved. Ammonia and hydrogen have zero CO₂ at combustion; by 2040, we expect a portion of the fleet to run on these, especially newbuilds. Wind assists (e.g., rotor sails) and other innovations can provide supplementary power that effectively lowers fuel usage and counts as a zero-emission technology (if properly certified under Annex III). Many vessels by 2040 might sport such technologies to help meet the 31% and 62% reduction targets.

- Financial Implications and Opportunities: The penalty structure will likely be adjusted over time. The regulation allows updating the penalty factors to reflect energy prices. Shipping companies should watch these adjustments. In the long-term financial planning, include carbon pricing integration: by 2030, shipping in EU ETS will cost money per ton of CO₂; by 2050 similar schemes may exist globally. These act as additional “penalties” for emissions, so fully switching to zero-carbon energy not only avoids FuelEU fines but also emissions trading costs – reinforcing the business case by mid-century. On the positive side, green financing might help fund the transition: e.g., issuing green bonds to retrofit a fleet for ammonia fueling, or getting lower interest loans tied to hitting emission targets.

- Resilience and Flexibility: Plan for a range of scenarios. What if by 2040 e-fuels are still pricey? The company should still be able to comply perhaps by having more efficient ships and using some biofuels. What if a breakthrough (say nuclear propulsion or something radical) comes? Stay flexible to adapt. Business continuity will depend on not betting on one solution too early – hence many opt for dual-fuel or “fuel-ready” designs to keep options open. For instance, ordering a ship that is ammonia-ready (space and provisions for future ammonia fuel) but initially runs on VLSFO means you can retrofit when ammonia becomes viable. This hedges against uncertainty.

Beyond Compliance – Sustainability Leadership: By 2050, the goal is climate-neutral shipping. Companies should align FuelEU compliance with their broader Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG) strategies. Those that aim to be zero-emission well before deadlines will likely influence the market and potentially policy (perhaps enjoying incentives or preferences). The roadmap thus becomes part of corporate strategy: some lines have set targets like “net-zero by 2040”, effectively overshooting FuelEU goals. This may seem costly but can future proof the business.

In summary, the compliance roadmap starts with immediate actions to monitor and slightly tweak operations (2024-2025), then scales up with significant fuel and technology changes by 2030 and culminates in a transformed fleet and operations by 2050. It is crucial to integrate this roadmap with financial planning and fleet strategy to ensure business continuity – shipping firms must remain profitable while meeting regulatory demands. The companies that manage this integration best will not only survive the energy transition but thrive in a decarbonized shipping landscape.

5. Numerical Analysis: Fuel vs. Penalties

One of the most critical decisions for compliance is whether to use more costly alternative fuels or pay the FuelEU penalties (and/or purchase compliance credits). A cost-benefit analysis helps illustrate this choice, often varying by route type.

Let’s break down two scenarios with simplified hypothetical calculations:

- a) Intra-European Voyage (EU-EU route): Consider a ship on a voyage entirely within the EU (e.g., Antwerp to Barcelona). Suppose in one year it uses 10,000 tonnes of fuel (heavy fuel oil equivalent) on EU voyages. Under FuelEU, 100% of that energy use counts towards its GHG intensity requirement. For 2025, the ship needs a 2% reduction in GHG intensity relative to 2020. Achieving a 2% reduction could be done by using about 2% of a zero-carbon fuel in the mix (this is a simplification; 2% by energy roughly yields 2% emissions cut if the substitute is near-zero carbon). So the ship would need to use ~200 tonnes of alternative fuel (replacing 200t of HFO) to meet the target.

- Alternative Fuel Cost: If the alternative fuel is, say, biofuel costing an extra €500 per tonne compared to HFO, then 200t would cost an extra €100,000. (This assumes HFO at €600/t, biofuel at €1,100/t, for example.)

- Penalty Cost: If the ship chose not to use any cleaner fuel (thus failing the 2% target by the equivalent of 200t fuel worth of emissions), it would incur a penalty. Using the earlier figure of ~€2,400 per excess tonne, the penalty for 200t excess would be €480,000. This is nearly 5 times higher than the cost of simply using the biofuel in this example. Even if these figures vary, the structure is such that the penalty is designed to be higher than the typical cost of compliance. Indeed, an analysis by a maritime consultancy showed that for a 15,000 TEU containership, the FuelEU penalty could be about 9% of its annual fuel bill – a significant cost increase that diligent compliance can avoid.

- Thus, for an intra-EU voyage, it’s economically favourable to use the required amount of cleaner fuel rather than pay the penalty, if the alternative fuel price premium is less than the penalty rate. The breakeven premium in this scenario would be up to €2400/t; most biofuels and even e-fuels are expected to have lower premiums than that per ton of fuel energy.

- b) EU-non-EU Route (one EU port, one non-EU port): Now consider a voyage from an EU port to a non-EU port (e.g., Hamburg to Singapore). Suppose the ship again uses 10,000 tonnes of fuel for that round trip. Under FuelEU, only 50% of the energy is considered (since one end of the voyage is an EU port, the other is outside the EU). So effectively, 5,000 tonnes count toward the requirement for that ship. The other 50% (the non-EU half) is outside FuelEU’s scope (though still subject to EU ETS for the EU half and possibly other regimes down the line).

For 2025’s 2% target, the ship would need to offset 2% of 5,000t = 100 tonnes of fuel-equivalent emissions. This could be done by, for example, using ~100 tonnes of alternative fuel on that voyage (or cutting equivalent emissions through efficiency).

- Alternative Fuel Cost: Using the same price difference assumption (€500 extra per ton for biofuel), 100t costs an extra €50,000.

- Penalty Cost: If the ship did nothing, it would miss the target by 100t and face a penalty ~ €2,400 * 100 = €240,000.

Again, compliance (100t of clean fuel) is much cheaper than non-compliance. However, one might note that since only half the fuel is counted, the absolute cost is lower than the intra-EU case. Some operators may be tempted to think they can “get away” with less action on these routes, but the penalty still quadruples the cost of inaction in our example.

Route Comparison Table:

For clarity, consider the above scenarios in a simplified table:

|

Scenario |

Fuel Use (t) |

Counted by FuelEU |

Needed Alt Fuel for 2% |

Alt Fuel Extra Cost |

Penalty if Non-Compliant |

|

EU–EU voyage |

10,000 t |

100% (10,000 t) |

~200 t (2% of total) |

~€100k (at €500/t premium) |

~€480k (200 t * €2400) |

|

EU–NonEU voyage |

10,000 t |

50% (5,000 t) |

~100 t (2% of counted) |

~€50k (at €500/t premium) |

~€240k (100 t * €2400) |

Assumptions: Penalty €2400 per excess ton (approximate for 2025), alt fuel premium €500/t. These are illustrative; actual prices will vary.

The table illustrates that paying penalties is economically inefficient compared to investing in cleaner fuel for both types of routes. FuelEU’s design essentially taxes excess fossil fuel use at a high rate to drive behaviour change.

However, there may be edge cases to consider numerically:

- so, by 2030 if fuel prices shift, the €2400/ton figure might be higher.

- Energy Efficiency vs Fuel Switching: Another numerical consideration is that not all compliance needs to come from expensive fuels; some can come from efficiency improvements which save fuel (and money). If a ship manages to reduce its overall fuel consumption by 2% through speed or tech, it meets the 2% intensity target without any extra fuel cost – in fact saving cost. For example, our EU–EU voyage ship using 10,000t could instead aim to use only 9,800t through efficiency; then its GHG per MJ is down 2% inherently. The cost of such efficiency might be crew effort or a one-time upgrade like a new propeller. Thus, a cost-benefit analysis often shows that operational measures (which might cost little or even save money by burning less fuel) should be done first, before buying expensive alt fuels or paying penalties. This layered approach (first reduce consumption, then substitute fuels, lastly pay penalties if needed) is how many will minimize total cost.

- Pooling Economics: The regulation’s flexibility means if one ship can’t economically justify alternative fuels, a company could offset it with another ship. Numerically, if Ship A on EU–EU route finds alt fuel too costly, but Ship B on another route has switched to 10% biofuel (exceeding its requirement), the surplus from B can cover A. The cost is internalized: essentially, the cost Ship B spent on extra biofuel vs what Ship A would have paid in penalty. If Ship B’s biofuel cost was less than the penalty that A would incur, the company saves money overall. This internal carbon credit trading will likely follow a least-cost logic: invest in reductions where it’s cheapest first.

To sum up, the numerical analysis strongly favours proactive compliance. Even when considering different routes:

- For intra-EU voyages where 100% emissions are regulated, the volume of alternative fuel or efficiency needed is higher but so would be the penalties – making compliance the clear choice financially.

- For EU to non-EU routes, only half the emissions count, so the requirement is effectively halved, but the logic remains the same. It might slightly reduce the urgency (since half the fuel can be conventional without penalty), but any non-compliance portion still faces steep fines.

The conclusion is that investing in cleaner fuels and efficiency tends to be cheaper than paying FuelEU penalties in most scenarios, which is by design. Companies will run these analyses for their specific ships and routes (there are even calculators being provided by exchanges and consultants, but the broad outcome is to use these numbers to justify decarbonization investments. Furthermore, as alternative fuel production scales up, costs are expected to come down, whereas penalties may rise with inflation or increased stringency – tilting the equation even more in favour of using clean fuels.

6. Business Model Considerations

FuelEU Maritime is not just an environmental regulation; it’s poised to reshape business models in the maritime industry. Key considerations include:

Decarbonization as a Core Strategy: Shipping companies traditionally focused on scale and fuel efficiency for cost reasons; now carbon efficiency becomes equally important. This regulation forces companies to integrate fuel strategy into their business models. For liner operators (container lines, ferry services), we may see green corridors emerge – specific routes where they deploy their greenest ships and offer lower-emission transport, potentially at a premium. Tramp operators (bulk, tankers) may incorporate carbon clauses in contracts and differentiate their service by offering compliance assurances. Some may even pivot business models to become “energy managers”, optimizing fleets to minimize carbon costs (including ETS, FuelEU, etc.). In effect, compliance and sustainability performance will be a competitive parameter like price and reliability.

Impact on Shipping Costs and Trade: Compliance costs (fuel, technology, or penalties) will likely translate into higher shipping costs, at least in the medium term. This could marginally increase freight rates, especially on EU-related trades. Shippers (cargo owners) might have to pay more for low-carbon transportation. However, there could also be market-based adjustments: if some trades become expensive due to FuelEU, shippers might seek alternatives (e.g., more transshipment outside EU to minimize voyages counted, or even shift to rail/road for intra-Europe if costs diverge). The regulation tries to prevent evasion via neighbouring ports by counting 50% even then, but cargo could still route differently (e.g., an Asia-Europe container could be transhipped at Tanger Med in Morocco – 50% of that leg counts, but a short feeder into Spain from Morocco also 50%, overall the journey has some reductions in accounted fuel compared to direct Asia-EU? These complex routing choices will be evaluated by liners). Short sea shipping in Europe, which is fully under FuelEU, might see cost increases that could affect competition with land transport. Yet the EU likely will also push other sectors (like trucking) to decarbonize, so all transport modes face pressure.

Existing vs New Vessels: FuelEU will impact vessel asset values and charter markets. Newer vessels or those built with advanced tech will be in demand, whereas older, inefficient vessels could struggle to find employment on EU trades. For example, an eco-design bulk carrier (say built 2020 with efficient engine) will have an easier time complying than a 2006-built vessel – charterers might start preferring the former to avoid FuelEU complications. This could create a two-tier market: “FuelEU-compliant” ships commanding better rates for EU voyages, and older ships possibly being discounted or sent to other regions. Fleet renewal decisions will accelerate – shipowners may scrap or sell older ships and invest in new ones with dual-fuel engines that can burn methanol or LNG now and convert to ammonia/hydrogen later. Over the next decade, as many ships reach 20-25 years age, the calculation will include “will this ship be able to cost-effectively meet 2030/2035 requirements?” If not, it’s a candidate for early retirement.

Charter Party and Commercial Terms: We have touched on how charter parties will adapt. In essence, contracts need to allocate FuelEU responsibilities in a fair way. BIMCO’s new clauses (one for time charters, and likely one for ship management agreements) will become standard. This changes business negotiations: a time charterer might accept costs for biofuel but in return might negotiate a lower hire rate. Or owners might say “I’ll handle compliance, but I’ll charge extra for it.” Also, time charter duration choices might be affected – a charterer may not want to take a vessel for 5 years if uncertain about compliance in later years; conversely, an owner might be hesitant to commit a ship long-term without clauses that protect them if regulations tighten. We might see flexible charter clauses that allow switching vessels or adjusting terms if a ship’s compliance becomes problematic (for instance, if a ship consistently incurs penalties, perhaps the owner can substitute a different ship, or the charterer can demand more biofuel use).

Fuel Suppliers and Bunker Industry: The maritime fuel supply chain will also change. Bunker suppliers will diversify into providing biofuels, LNG, methanol etc. Some may offer turnkey compliance solutions – e.g., selling a package of fuel plus certificates ensuring its sustainability. We could see contracts where a bunker supplier guarantees that using their fuel will meet FuelEU targets (backed by emissions data), effectively taking on some compliance service role. Additionally, new businesses like emissions credit brokers or FuelEU pooling facilitators might emerge to help ships trade compliance surpluses/deficits. This is like how the EU ETS created carbon trading desks at companies – FuelEU could drive creation of internal carbon-accounting teams in large shipping firms and new services by consultancies.

Sustainability and Brand Value: Shipping lines are increasingly aware of customer pressure to decarbonize. FuelEU compliance can be leveraged in marketing – e.g., advertising that 100% of your European shipments are done with 6% renewable fuel (meeting 2030 target) could be a selling point, especially as big cargo owners (Amazon, IKEA, etc.) have their own climate pledges. Thus, the business model might shift from purely moving goods to providing low-carbon logistics solutions. Carriers might also diversify into energy – for instance, some large shipowners might invest in fuel production (we’ve seen examples like Maersk investing in methanol fuel plants) to secure supply and control costs. So, a portion of a shipping company’s business model might become fuel production or co-investment in energy projects, which is a big shift from the traditional model.

Regulatory Risk Management: Businesses will incorporate managing regulations into their models. FuelEU Maritime is one region’s rule; others may follow (perhaps China or other major jurisdictions could impose similar rules for their ports in the future). Companies might set up internal compliance units that handle ETS, FuelEU, IMO CII, etc., in an integrated way so that decisions (like which ship to put on which route) consider multiple regulatory impacts. For instance, the EU ETS will cost a certain amount per CO₂ ton emitted on EU voyages, and FuelEU adds an intensity requirement – both need to be managed. If a ship must buy EU ETS allowances (or the charterer does) and faces FuelEU penalties, that’s double cost for the same emissions. However, using cleaner fuel saves on both counts (less ETS cost and no FuelEU penalty). Smart business planning will optimize across these: maybe a company buys an extra cleaner fuel to avoid not just FuelEU fines but also to reduce ETS allowance purchases. This combined approach could be formalized in their model as a “carbon cost per voyage” metric that they minimize.

Competitiveness of EU Shipping: One concern is if non-EU operators have an advantage by avoiding EU routes. However, since FuelEU applies to any ship entering EU ports regardless of flag, and you can’t avoid it if trading with EU, the playing field within that market is level. In global competition, an EU-focused ship might have higher costs, but many global customers demand emissions reduction everywhere, not just EU. Also, IMO is moving in the same direction albeit slower. So, in terms of business model, most large shipping companies are global and will likely extend these measures fleet-wide eventually. Some niche operators might decide to stay out of EU trades if it’s too costly, but that also limits their market.

Fleet Portfolio Management: A possible model emerging is companies maintaining a portfolio of vessels with different capabilities and deploying them optimally. For example, a shipowner might keep a couple of high-end dual-fuel ships for their EU business and use older ships in regions with less regulation (Africa, some Asian routes) until those regions also tighten rules. Essentially, carbon regulation becomes a factor in where you send your ships – high regulation areas get the best ships. This is analogous to how some vessels are assigned to ECA zones because they have scrubbers or burn low sulphur fuel, while others avoid ECAs because they only can burn high sulphur fuel cheaply. Over time, as global standards catch up, that arbitrage closes. But in the intermediate, business models will consider how to maximize profits by smartly allocating assets under varying rules.

Charter Rates and Asset Values: The cost of compliance might get capitalized into charter rates. We could see “eco-ships” earning a Green Premium – already eco-design ships get a few thousand dollars more per day due to fuel savings; in future, also due to avoided carbon costs. Conversely, ships that are liabilities under FuelEU might find it hard to get charters or must accept lower rates (or trade exclusively in less regulated markets). Financial institutions are watching this via the Poseidon Principles (which measure the carbon intensity of financed ships). If a ship consistently doesn’t meet FuelEU standards, banks could be reluctant to refinance it. So, business models that rely on older, high-emitting ships will face not just regulatory costs but financing and insurance challenges.

Collaboration in the Industry: FuelEU might drive more collaboration between shipowners, charterers, cargo owners, and even competitors. We might see joint ventures for fuel sourcing (pooling demand to get better price for biofuels), shared infrastructure (like partners investing in a bunker barge that supplies green methanol in a region), or even vessel-sharing agreements based on emission profiles. The traditional model of fierce competition could give a bit of way to cooperation when it comes to building expensive new infrastructure or fueling networks – because no single company can do it alone at reasonable cost.

Resilience and Adaptation: Finally, business models will incorporate greater resilience to regulatory and energy shifts. Scenario planning (peak oil demand, hydrogen economy scenarios, etc.) will inform strategy. Shipping has always dealt with volatile fuel prices; now it will also deal with carbon price volatility and evolving standards. Companies might build in contractual safeguards (like clauses to renegotiate if regulation changes drastically mid-charter). Being nimble and adaptive becomes a business model virtue.

In conclusion, FuelEU Maritime is likely to accelerate the transformation of shipping business models towards sustainability. What used to be a relatively straightforward business of moving cargo now involves carbon management, alternative fuel logistics, and closer partnerships across the supply chain. The industry’s structure might shift – possibly energy companies playing a bigger role in shipping or shipping companies in energy. Those who innovate in their business approach – turning compliance into part of their service offering – will find new opportunities (e.g., attracting customers willing to pay for green transport). Meanwhile, those clinging to old models (cheap ships, cheap fuel without regard to emissions) will find it increasingly hard to compete in markets touched by EU regulations and the broader decarbonization push. FuelEU Maritime, along with its sister regulations like EU ETS, essentially mainstreams sustainability in maritime commerce, pushing the industry to align profitability with environmental performance.